INTERVIEW: In conversation with Kate Bush of Media Space

Earlier this month, the first UK solo exhibition of Magnum photographer Alec Soth opened at Media Space, a still relatively new and highly innovative gallery space dedicated to photography and located within the Science Museum, London. The London Photography Diary, in collaboration with Hemera, had an opportunity to get a first glimpse of the exhibition and speak to head of photography Kate Bush about her thoughts on Soth’s work and methods for curating this impressive mid-career survey entitled Gathered Leaves: Photographs by Alec Soth.

The exhibition forms a dynamic experience, progressing chronologically through lyrical displays of Soth’s four main series to date, Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004), Niagara (2006), Broken Manual (2010) and Songbook (2014, seen here for the first time in a UK show). Photographs in book and newspaper format and those framed and hung in a variety of sizes are in ready dialogue with the array of conceptual materials that informed Soth’s projects. The set-up reflects a combination Kate Bush’s non-invasive but no less creative curatorial approach and Soth’s restless experimentation across the many forms that photography can take, from prints and books to zines and digital media.

Fangfei Chen:

Could you please introduce your role as the head of photography for the Science Museum Group? Why did you choose to exhibit Alec Soth’s work in this museum specifically?

Kate Bush:

I serve as head of photography at the Science Museum Group and I work across the museums in the group – so I have a role at the National Media Museum in Bradford, in addition to my responsibility for the programming at these beautiful new galleries called Media Space on the second floor of the Science Museum.

The intention behind Media Space is to create a new destination for national and international visitors, lovers of photography, and we’re going to do that in two ways. Firstly, we are going to work to bring to public attention the fantastic, incredible collection that belongs to the Science Museum. It’s one of the best collections in the world, particularly in the early period of photography and from the beginnings of photography up to the First World War, an absolutely exceptional collection.

We also have a very strong British documentary collection – but the idea behind the Media Space programme is that we are both profiling and allowing people to share this marvellous collection alongside exhibitions that are being made by international photographers, living and dead. So we have two gallery spaces and the idea is to continually juxtapose historical projects with contemporary projects.

We’re pleased at present to be opening a major new exhibition by Alec Soth, who is one of the most significant mid-career photographers in America working today.

Elizabeth Breiner:

Soth speaks about not being a big believer in documentary truth, and in his work explicitly tries to experiment with this as a concept, test its limits, even undermine it… As with the Fontcuberta exhibition earlier this year, it seems as though the Science Museum has a particular interest in toying with or even revealing the fallacy of the idea of any real documentary truth, and I wondered if you think there’s a deliberate irony in displaying these types of work within a science museum or if it says something about the unconventional nature of the space itself?

KB:

I don’t think we’re intending to be ironic in the programming at Media Space – what we want to do is represent the breadth of photographic practice. Sometimes those projects will have particular emphasis on science and technology, but equally they may not, and I think it’s sort of a question of creating an identity for a new photography programme that is located in a science museum but isn’t necessarily just about science.

And of course, at the heart of photography there’s always been this historical mixed identity, or double identity if you like, whereby it’s always been a form of technology; and, indeed, when it was collected by the Science Museum it was treated as chemistry. So it is a technology but it’s also become an art form.

Next door, we have a display by Julia Margaret Cameron, one of the incredibly influential pioneers who really worked to establish photography as an expressive art form in its own right. So I’d say we’re not programmatically going down a particular route, I think the intention is really to represent the photographic medium today in as wide and varied a form as it takes.

FC:

Where does the exhibition’s title Gathered Leaves come from? The idea of gathering leaves is interesting – in a sense, like the process of preparing a book and gathering materials page by page. How does this idea relate to Soth’s photographic practice?

KB:

The title of the exhibition is Gathered Leaves, and that title came from Alec at an early point in the process when we were working out how to give the show its very particular identity. And one of the early ideas, which we express in this show, is the relationship to the books, the books that Alec is very well known for, and the printed photograph in a framed form, in an exhibition form. In every room we create a conversation between the project in printed form and as a framed print on the wall.

So in one sense Gathered Leaves simply means the gathering up together of sheets of paper, which essentially is what photography is – apart from when it’s in a digital format, of course. At the same time it’s a direct reference, a quote from Walt Whitman’s American epic poem ‘Song of Myself’, which he wrote in 1855 as America was on the eve of civil war. In that poem, Walt Whitman wanders through the nation and notes many different facets of people in society and so on. There’s also a very important idea in that poem about the relationship of the self with the world and the cosmos.

I don’t think Alec would want to compare himself to Walt Whitman because he’s far too unpretentious to do that, but I think it’s sort of a guiding theme that evokes a little bit of what I think he’s setting out to do. I think this is a photographer who is making a very big body of work, it’s an epic body of work, and it’s a body of work in which he himself is very much part of the thought process of it – sometimes he appears literally in the work – but I think he’s always very conscious of his subjectivity in the world when he’s photographing, in the way that Walt Whitman was with that poem.

FC:

Was the publication for Gathered Leaves created in conjunction with the curatorial process?

KB:

The publication for Gathered Leaves is not a traditional exhibition catalogue by any means, and in fact it was a project that Alec and Michael Mack, his publisher, embarked on in tandem, but also, in a way, to complement this exhibition. Basically, in the show we are doing a mid-career survey, even though we’re not calling it that, because we’re showing the four major bodies of work that Alec has made over the last ten years – and essentially, the Gathered Leaves book does the same thing. It does it, I think, in a really joyous and generous way.

What they’ve done, rather miraculously, is to shrink the four books. Only one of those, Songbook, is still in print, and it’s very, very difficult to get Sleeping by the Mississippi and Niagara, and Broken Manual was only ever published in a very, very small edition, so what Michael and Alec have done is create miniature versions of each of the four books; and they arrive in a box, rather like a beautiful box of chocolates that you open, and you can literally read everything and see everything that was in the original books. So it’s like a kind of mini survey in a box, just as an exhibition is a type of survey in a box.

FC:

During the artist tour [given by Soth during the press view of the exhibition], Soth suggests that the three-dimensional exhibition space creates certain challenges for interpreting and presenting his work. How have you taken advantage of this exhibition space – this three-dimensional format – to alter and enhance the relationship between the audience and these photographs?

KB:

I think one of the things to me that is very tricky about photography is the different forms and formats in which it exists, and the different relationships you have with it as a viewer. So whereas a painting is really only experienced in a gallery, where you are physically in front of it, a photograph can live in many places – and principally, of course, the book is the format that most great photographers want to work in.

And what we try to get at in this show is that all these different methods or media are valid in different ways. So in this exhibition, we’ve tried to dramatise the difference between a large framed print on the wall and the relationship you have with a book or a periodical or a zine. Obviously they are related, but still different, and I think you have a quite different physical relationship with a large, beautifully printed photograph that’s lit perfectly, that’s luminous on the wall, than you do with a book when you’re sitting down and experiencing a sequence and a narrative that the photographer intended. So they are different but related media, I would say.

EB:

To piggyback off these ideas you’ve mentioned about the viewer’s relation to the work, Soth has expressed often this interest in creating actual distance between himself and his subjects – especially in Broken Manual, where he deliberately elongated that distance between photographer and subject – and I wondered where you think the viewer comes into that dynamic, and if this disconnect between photographer and subject is something that you feel comes across, especially in a physical space such as this.

KB:

Well I think in a sense, the viewer is always the photographer’s proxy. I mean, you’re always in the position in relation to the image that the photographer has taken in relationship to that image. And I think Alec worked very carefully to create particular underlying structures and associative mechanisms to catalyse the kind of empathy or feeling that he had for the subject in front of him. And you can see him do that in all sorts of interesting ways. You know, in Songbook it’s about extrapolating lyrics from these very famous popular songs so that when you read that, it’ll trigger a memory or associative response.

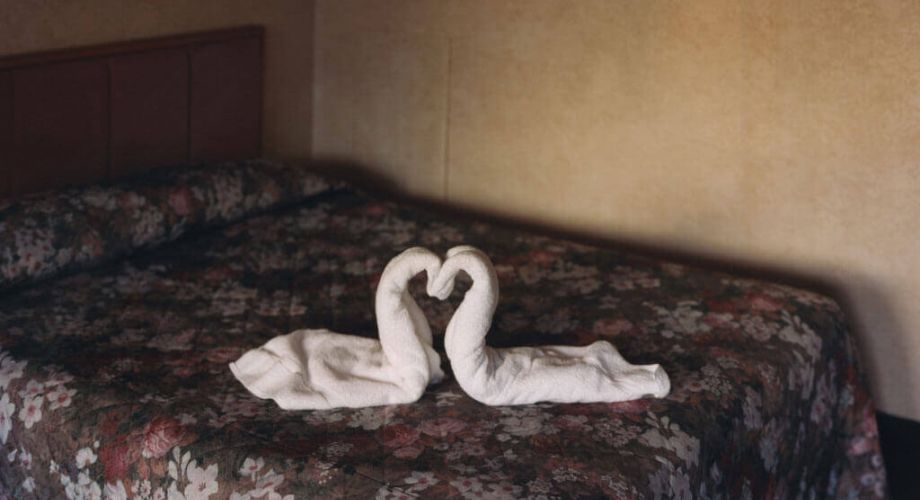

In Niagara, there’s often a very repeated motif that sometimes you can barely see or only notice if it is pointed out, but there are hearts, that sort of swim through those pictures in different places. And I think Alec is very conscious of the way that he works with his subjects… he says of the men in Broken Manual that he felt great tenderness towards them, because he can identify in a way with this desire to withdraw and this desire to find a very intense introspective space. As an artist, I think he identifies very strongly with that.

But then there’s another moment in Songbook that he’s very much in the world like a photojournalist going after that story, and he’s photographing it in a slightly more objective register, so you’re not quite as aware of his emotions in front of that subject. But nevertheless, I think there is always a movement between something that is joyful and full of humanity and something that is more of a romantic or sort of despairing or introspective position in the world. And that’s what I enjoy about his work, I think it has a very wide emotional range to it.

Exhibition information:

6 October 2015 – 28 March 2016, Media Space, Science Museum, London

Admission £8, Seniors £7, Concessions £6 (prices include donation)

22 April – 26 June 2016, National Media Museum, Bradford

Supported by: People’s Postcode Lottery

Principal Founding Sponsor: Virgin Media

Principal Founding Donor: Michael and Jane Wilson

Founding Donor: Dana and Albert R Broccoli Foundation

More info

Interview conducted by Fangfei Chen of Hemera and Elizabeth Breiner of London Photography Diary.