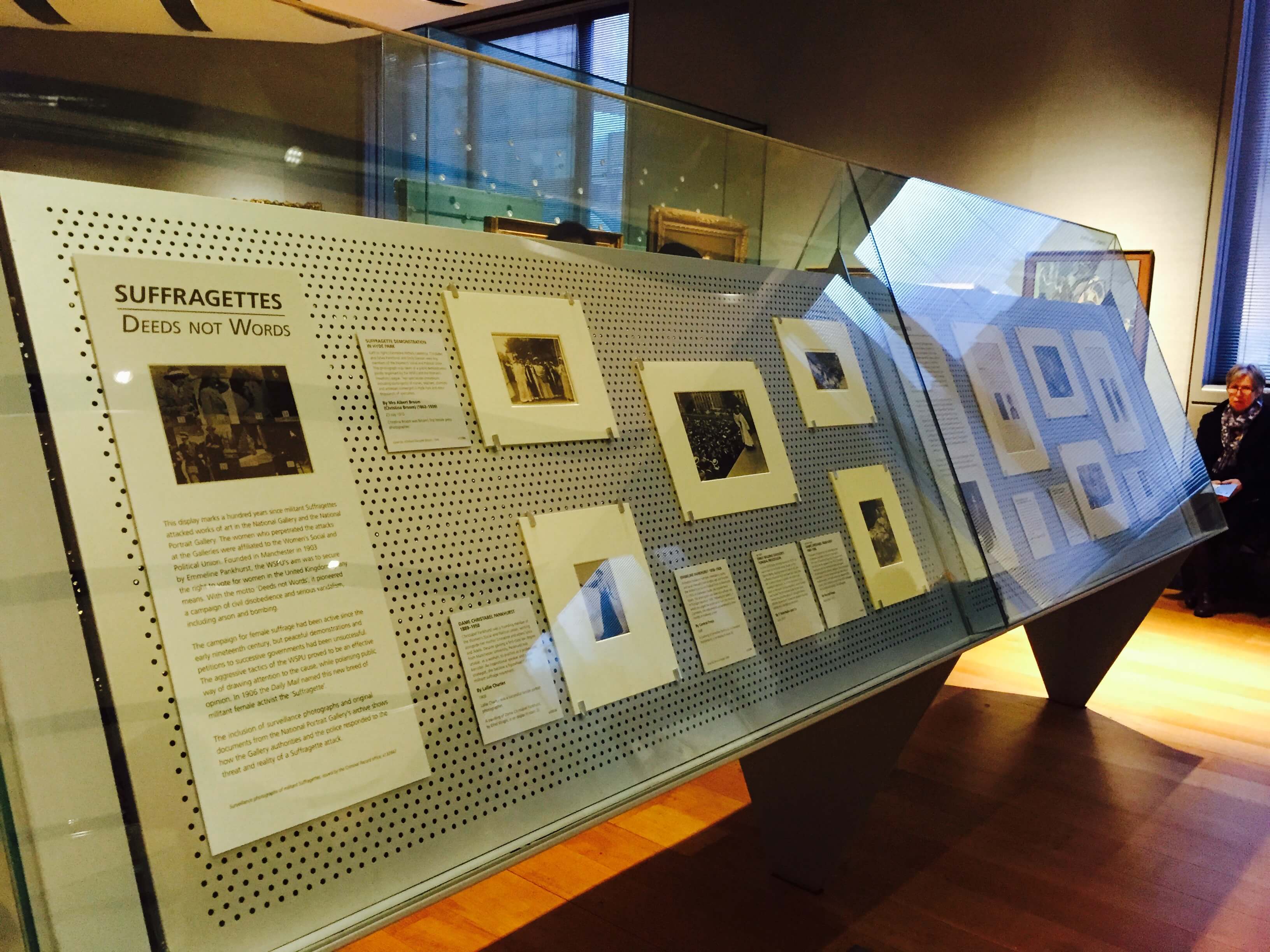

Hemera Collective meets Sheyi Bankale, curator of Photo50 at London Art Fair 2015 to talk about the exhibition ‘Against Nature’, his editorial and curatorial practice, and the current place of photography within contemporary art.

Kay Watson: Could you introduce us to the concept of the exhibition and why you chose it?

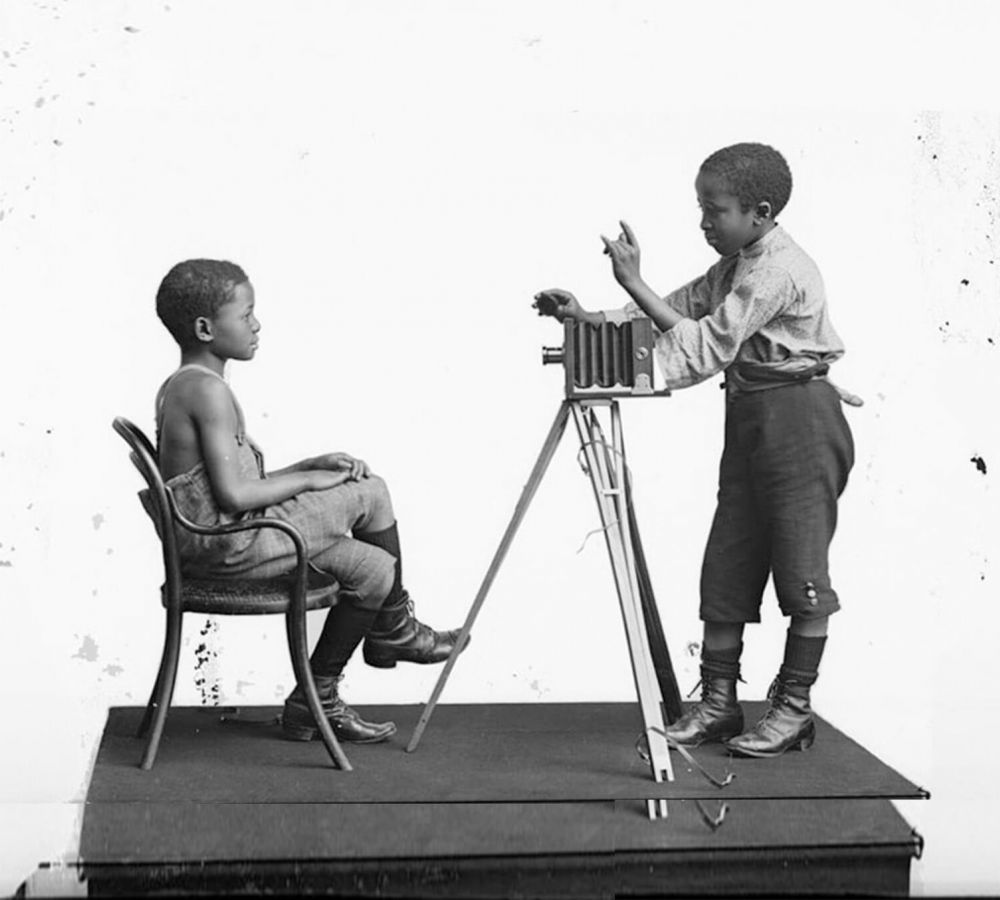

Sheyi Bankale: The exhibition Against Nature is a concept that I took from the book by Joris-Karl Huysmans of the same title. The relationship between objects and desire are themes which run throughout the book and I wanted to explore how they might be transcribed into an exhibition format. The book was published in the 1800s, around the same time as the invention of photography. It made a decisive break from traditional forms – away from realism and towards symbolism. So in a sense you had this literary world and this photographic world simultaneously breaking new boundaries. I found this parallel extremely interesting. It was equally an extremely prolific time in photography – there were so many different physical forms and processes within the medium. These concerns run throughout the show. Specifically, I wanted to consider photography as an object and try to identify how we view photography today, especially considering the massive shifts the medium has experienced.

The shift from the early 19th century to the 20th century saw the birth of the first 35mm camera, the 1960s saw the advent of colour photography, and one of the latest shift is, of course, the digital age. This digital shift is something that I wanted to address because we often look at images in a digital rather than physical form.

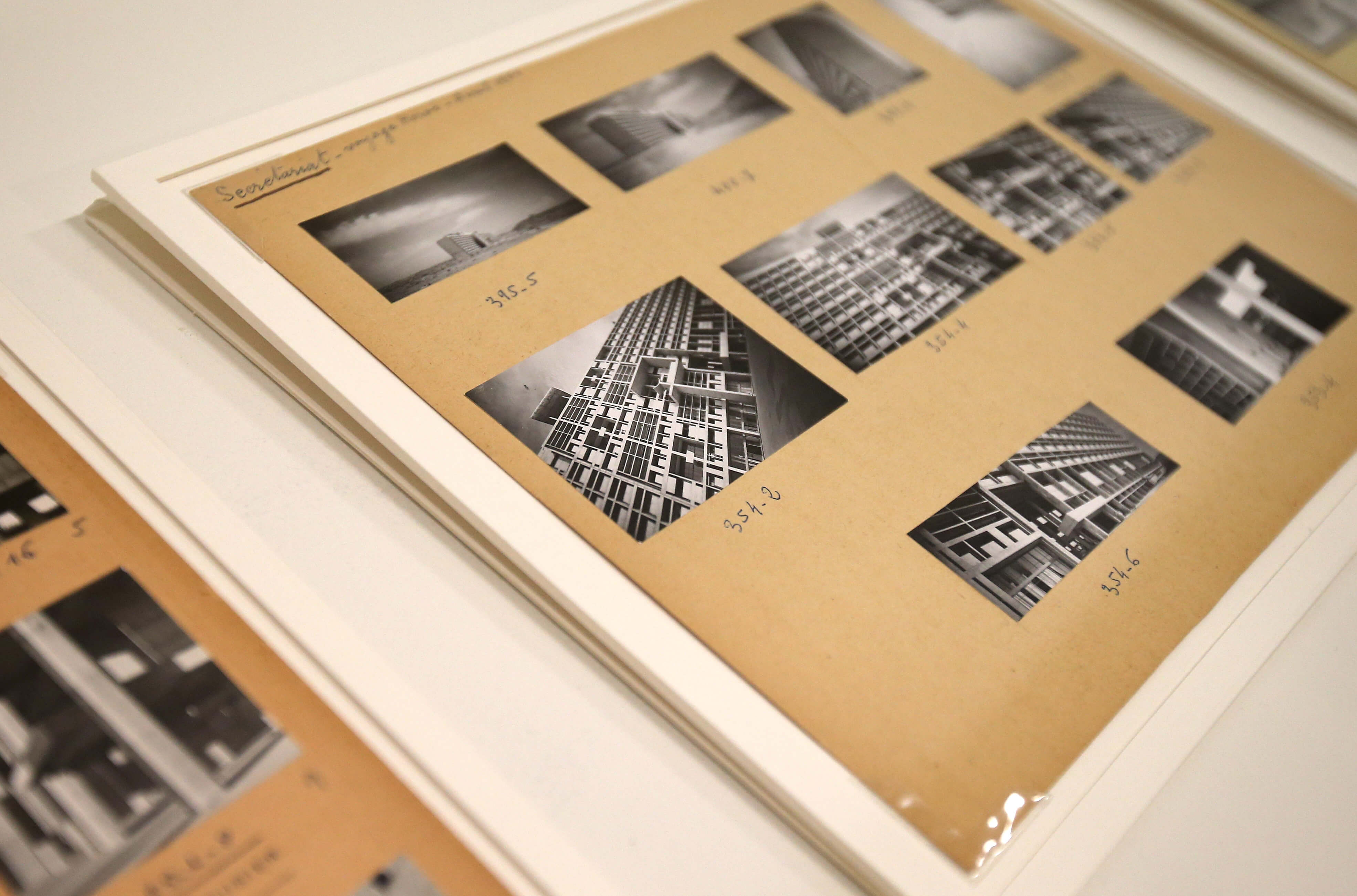

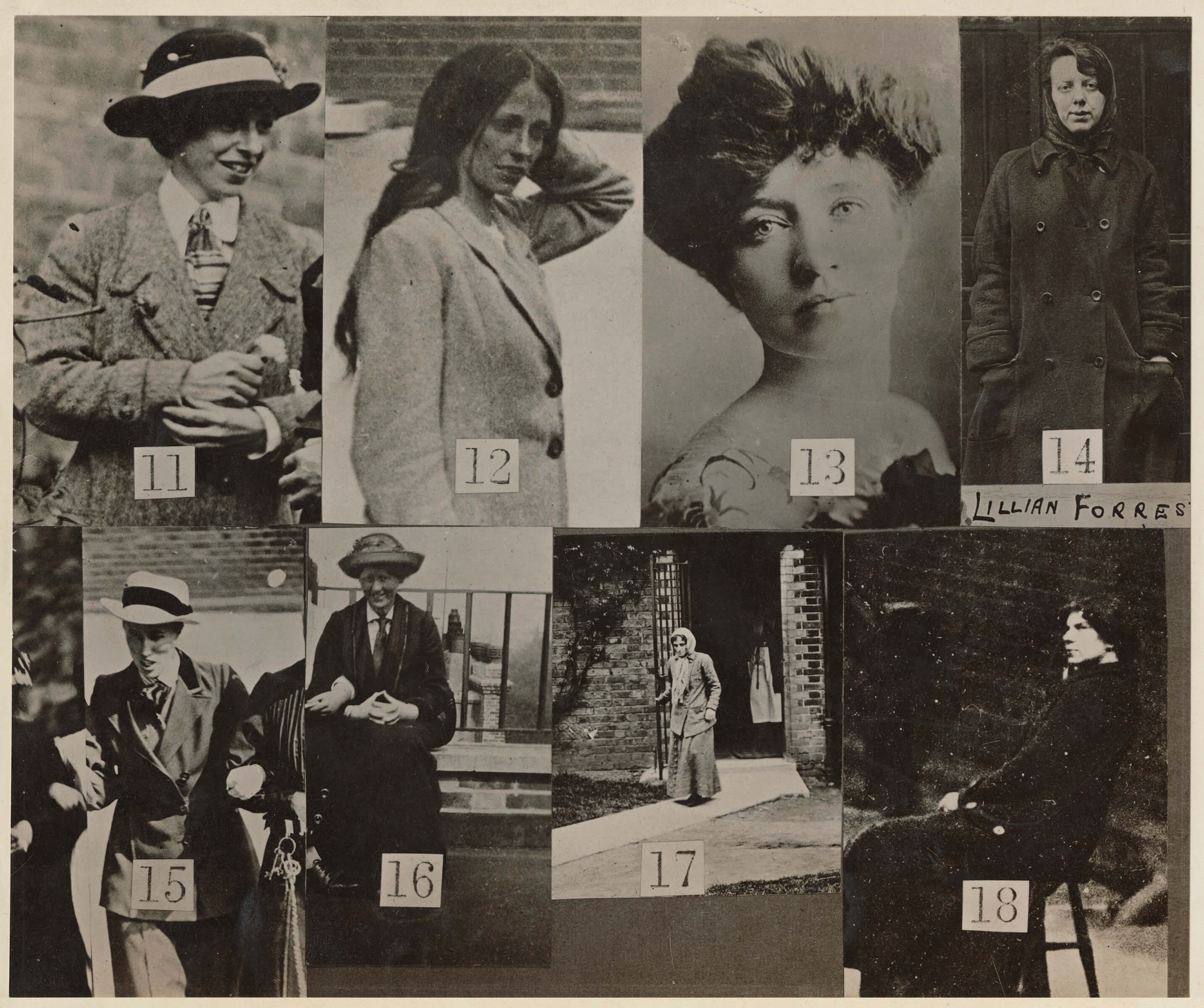

Nikolai Ishchuk, Leak X and Leak IX, 2014.

Jaime Marie Davis: So, how do we now view images and how can we change that through the exhibition?

What I thought it was really interesting to consider the digital plane and how photography is currently used within the medium. Many of the artists on show have adopted anachronistic approaches such as the photogram. They have tried to understand how different methods, processes and applications have shifted away from digital aspects. One example is Nikolai Ishchuk whose work is devoid of any functionality. He looks at the processes and material itself using some of the metals within aspects of photography to form solid sculptural objects.

J.M.D: As the largest photography exhibition ever staged in Finland Alice In Wonderland was one of the noteworthy projects of your curatorial career. The exhibition has some thematic links to Against Nature if we consider the notion of ‘constructing worlds’ or the relationship between the ‘real and unreal.’ Is this a continued line of inquiry in your curatorial practice?

S.B: My practice looks at metaphysical objects and ideologies within this world and considers how one might transcend an object and transcend the meaning of that object. So, you could say Against Nature is a sequel, in a sense, to Alice In Wonderland. But I look at photography as contemporary art and photography as a material-based medium that can shift and change and can have parallel existences. It can exist as a 2D print form but it can also exist as a material base in itself.

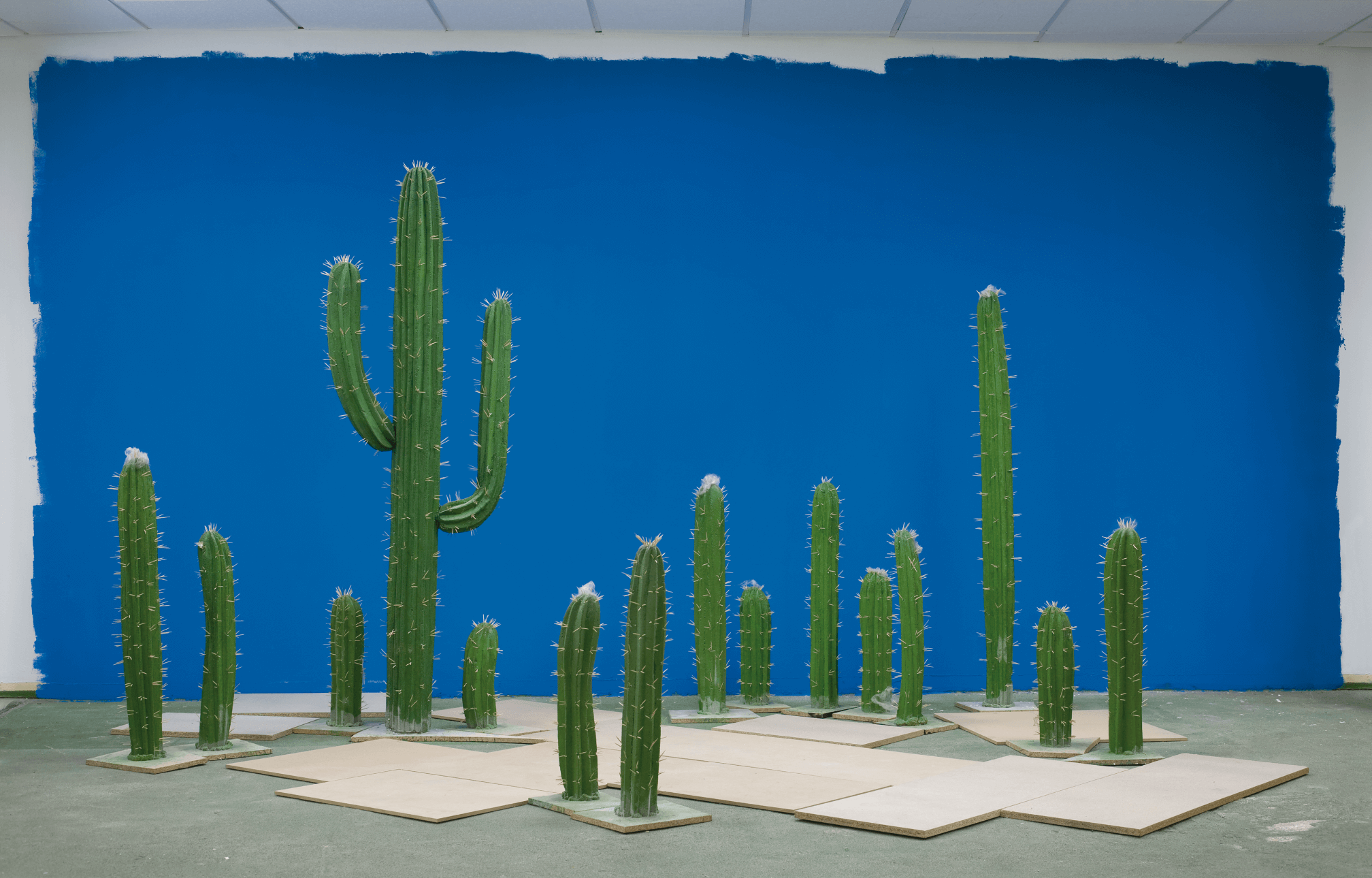

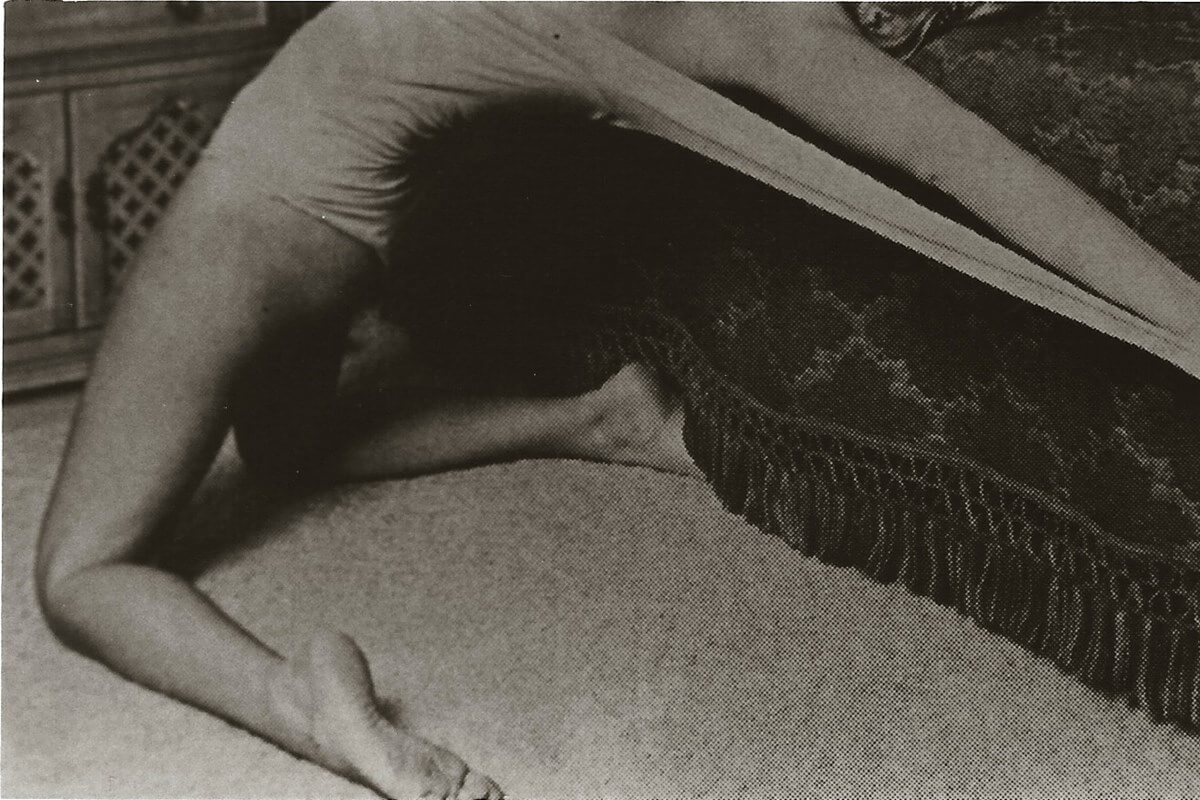

Alice and Wonderland was interesting because we were looking at artists globally who were trying to create a different vision of their work, as opposed to just the representation of a photograph. They were playing with surfaces and rendering ideas to create physical objects that were photographically based. Julio Galeote’s work is heavily indebted to a sense of ‘wonderland’. He looks at objects with a very different perspective, a dream state where an object is stripped of all its meaning and then re-represented, and documented as a photograph. Therefore, the photograph becomes the meaning of that new object. When you approach his work it looks like a regular photographic body of work, but when you start to understand his methodologies and ideologies, then all those different layers start to reveal themselves as an object versus a photograph.

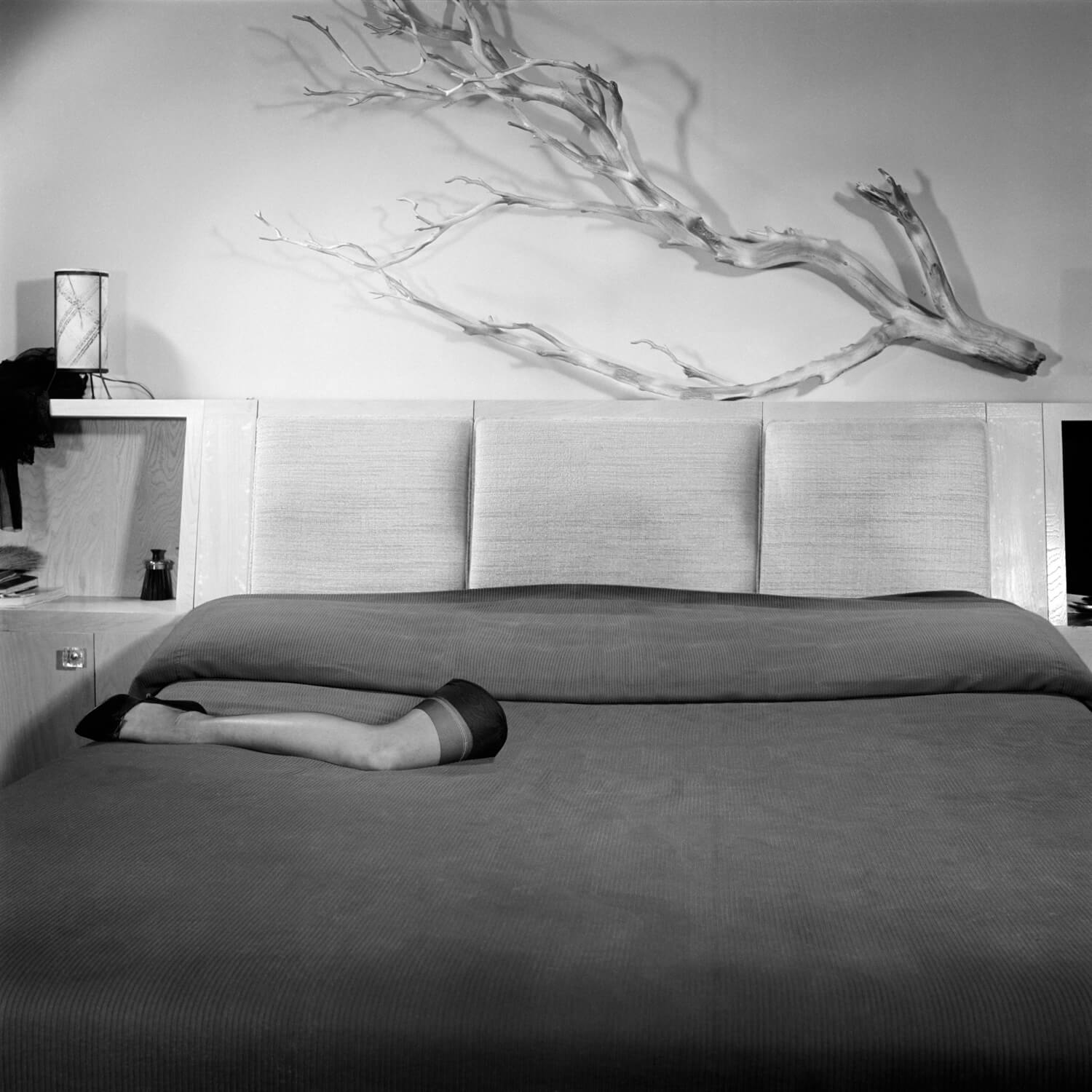

Julio Galeote, Excess n.1, 2012.

J.M.D: One thing that interests me is the way you work between editorial and curatorial roles, which have similar methodologies for constructing narratives. But they also deal with images differently as they move from static and viral to physical. How has your editorial role influenced your curatorial decisions, specifically in relation to the audience’s relationship to images as a physical encounter?

S.B: I think there is a parallel relationship between editorial practice and curatorial practice. They both work hand in hand and I don’t think one takes precedence. In a sense, the editorial is still a curatorial role within my practice – it’s working with words and images. I use the actual plane of the paper as a white cube and I have a very close relationship with the printer that I use because, for me, the publication is equally an exhibition space.

I find that the way editorial and curatorial differ, is in how the audience navigates through the space and digests the work. It’s a different feeling than the publication, which is a reception to the work versus an exhibition where it is transmitted. In the publication there is a mental digestion and, depending on who the audience is, they can extend that.

K.W: Thinking about the context of Photo50 within the London Art Fair – and Next Level, which looks at photography within the context of contemporary art – what do you consider to be the current position of the photographic image within contemporary art?

S.B: Photography is multifaceted. There are so many ways of thinking about it. Within the arts, there is a body of practitioners who conduct their practice as photographers. I think that is the issue as their practice can shift into different realms of photography such as editorial or commissioned work and there are so many different practices that take place within the medium of photography.

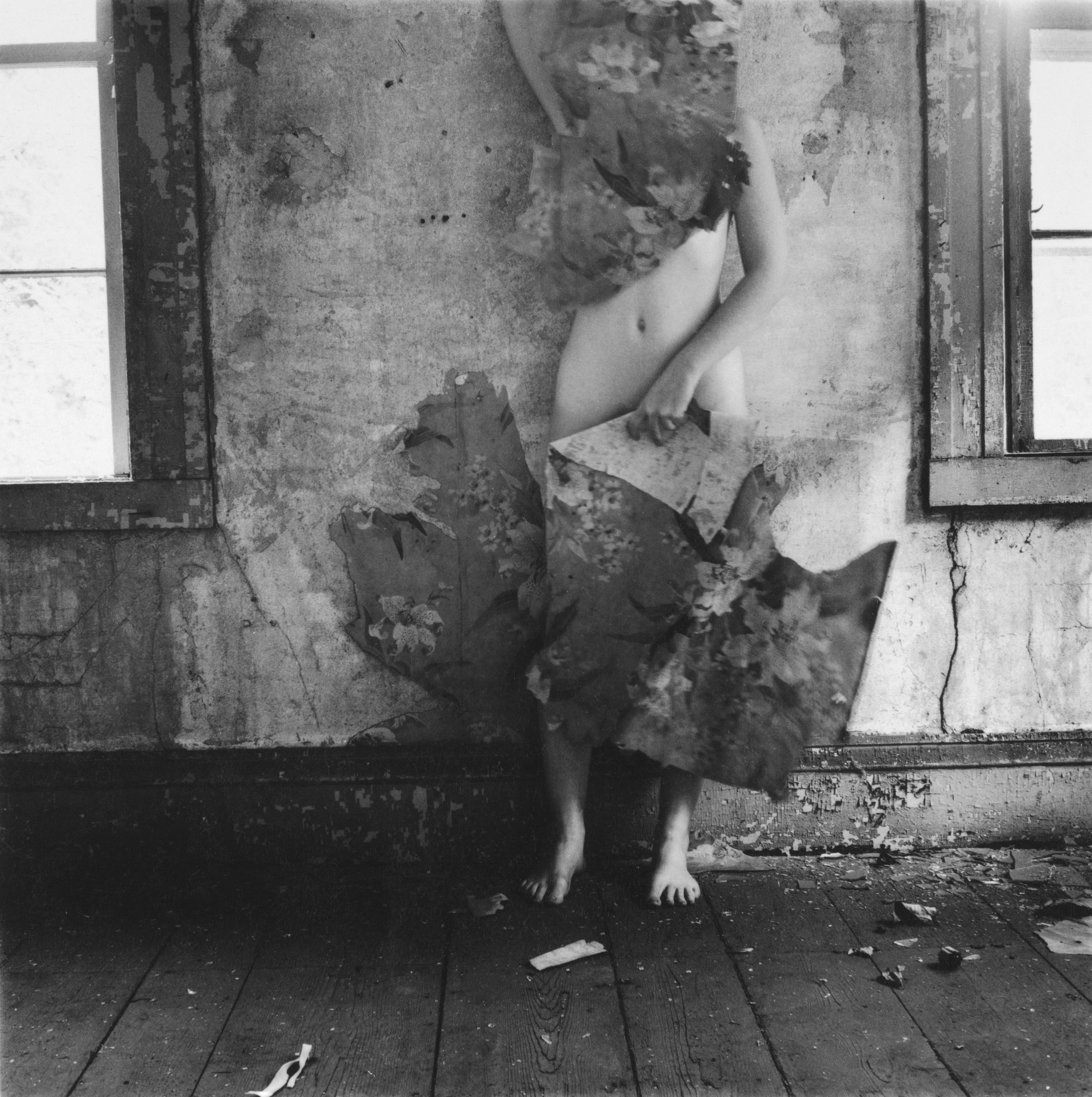

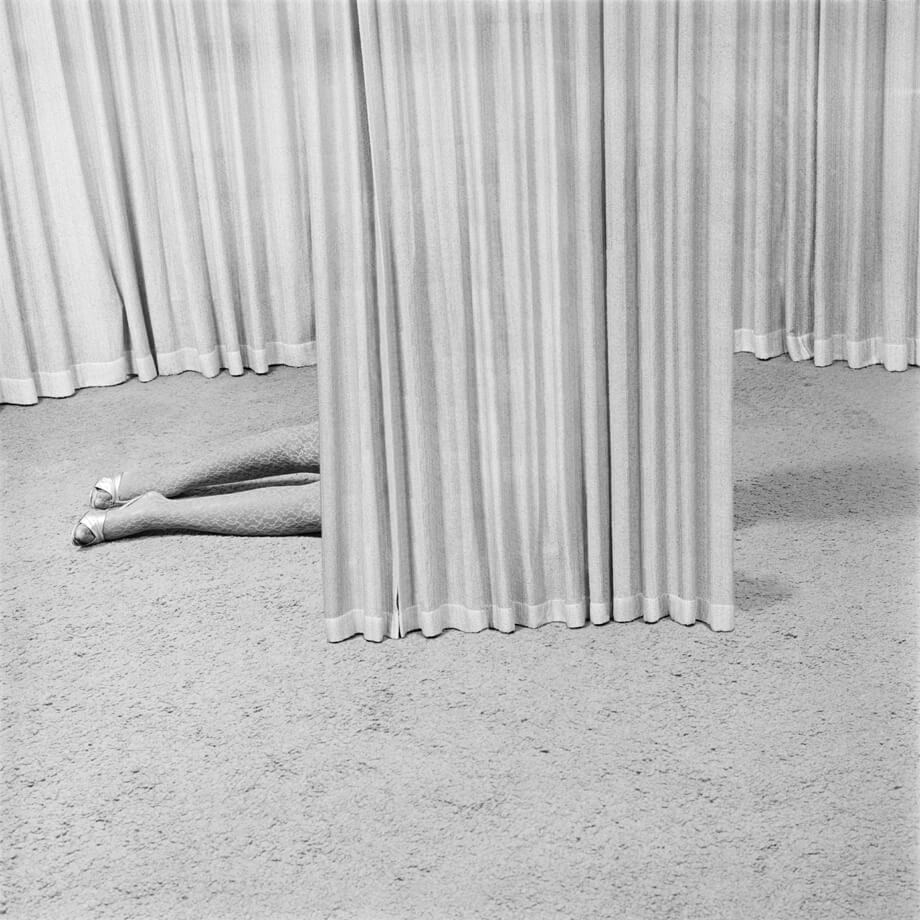

The question of whether photography fits within contemporary art is a divisive one. However I see photography as an art form. For me, it’s a medium that has a great fluidity within contemporary art. Especially now when we consider its form in the digital age, take for example the 3D representations of Jonny Briggs’. The beautiful aspect about photography is that it is always evolving; there is always a new application or process that is being applied to shape how we perceive photography today.

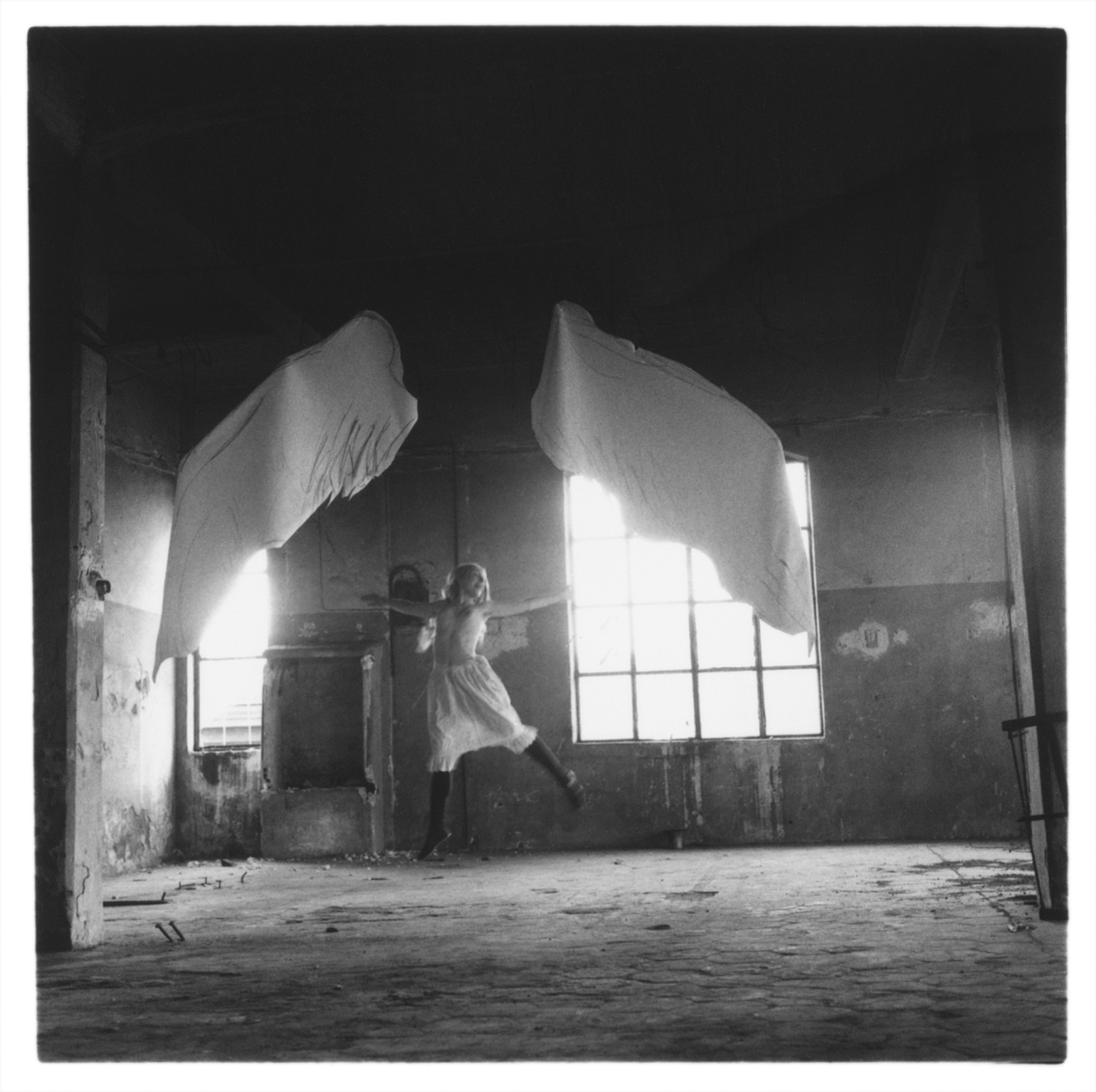

Jonny Briggs, Super Natural.

K.W: I also find this continually changing status of the photograph interesting, where a photograph used for one purpose, is then picked up to be used for multiple purposes between media. For example a post card is a photograph of a ‘view’, but is also something that is shared freely amongst people.

S.B: What’s really interesting, and who picks up on this is Darren Harvey Reagan. He looks at the subject or object that exists in the world, which is identified, then the photographic representation of that object and how that’s transmitted and, like you said, whether it’s tactile and exists for one viewer or shared amongst an audience, and finally photograph object itself or materiality of the photograph and its layers where the artists applies paints or different materials. )

J.M.D: Thinking about the literal meaning of the exhibition title, Against Nature brings to mind what I would say is a growing concern with what artists and other curators such as TJ Demos have claimed holds ‘essentialist thinking as much as gesturing towards a fantasy world apart from human activity’ and that we have entered a post-natural condition. Is this consideration of a ‘post natural’ condition also a double meaning or underlying concern given the included works by Julio Galeote such as his ‘Excess’ series?

S.B: Julio Galeote has a double entendre feel to his works and he definately touches deals with these issues. It’s also something that the book by JK Huysman alludes to, because one of the central characters isolates himself from human contact and creates a fantasy world within the home. The whole idea is that he is looking at how to shift meanings of objects and subjects within their plane. That is a challenge for a lot of artists and curators: to look at the fundamentals of nature, to return to areas outside of human existence and to have conversations along those lines. It’s a very small part of the exhibition but Julio’s work epitomises that. He hits on an important issue, one which, as you say, is of increasing importance in visual art discourses.

Business Design Centre

52 Upper Street

London N1 0QH

Miriam Otterbeck is the Deputy Editor of LPD.

Miriam Otterbeck is the Deputy Editor of LPD.

ena Haimes is a freelance arts and culture writer based in London. She studied at Goldsmiths College and the University of the West of England, and contributes to a range of publications as well as writing a visual arts blog.

ena Haimes is a freelance arts and culture writer based in London. She studied at Goldsmiths College and the University of the West of England, and contributes to a range of publications as well as writing a visual arts blog.

itia is a visual storyteller at heart and a marketing consultant by trade. She holds a BA from the University of Tasmania and studied Marketing, Advertising & PR at Queens University Belfast.

itia is a visual storyteller at heart and a marketing consultant by trade. She holds a BA from the University of Tasmania and studied Marketing, Advertising & PR at Queens University Belfast.